Everyone knows it; the tourist economy in Morocco plays an important economic role, not only in terms of the official GDP figures or of foreign exchange, but, even more significantly than that, with regard to the iceberg of the informal economy. In concrete terms, tens of thousands of people, and families, today find themselves without income.

Tourism has also played a major role in affirming Moroccan society as a welcoming culture and as a society constructively dynamic in its openness to the world and to the meeting of cultures.

So what is going to happen now? Are we going to see a profound change in tourist habits? Is this the end of cheap global travel? Is mass tourism doomed to disappear? No one knows, but whatever does happen, it is very likely that the return of foreign tourists to Morocco will take a long time, maybe several months. The outcome of the pandemic may well be that prudence takes over from the thirst for elsewhere, and the financial means of potential tourists will certainly and inevitably have decreased. The key question for Morocco is therefore to ponder what it is going to do in the coming year, which looks as blank as a clean sheet in the pages of its existence.

For the large majority of Moroccans, rural Morocco is a terra incognita.

If evidence is needed; several other countries dealing with the same problem have already begun to prepare themselves: it is an absolute necessity that national tourism save the annual high seasons, meaning that Moroccans must elect to travel within their own borders. The appeals to do exactly that are on the increase, and the Moroccan National Tourism Office has embarked on a campaign of public awareness on public television under the slogan #3lamantla9aw, which can be translated as meaning until we meet again, and which aims to awaken a reflex in Moroccans to choose their own country.

This initiative is commendable, but the challenge is nevertheless a difficult one because the lack of participation in national tourism has always been an issue in Morocco’s tourist economy. Now it will be a prerequisite to face these obstacles if these challenges are to be lessened.

The prime obstacle is the approach of tourist operators in Morocco, who have always considered the foreign traveller to be their target of choice. In fact, the Moroccan traveller often does not feel welcome, especially if he wishes to stay in a hotel. He knows this all too well, and the accommodation providers also make him feel it. Secondly, the pricing of accommodation is far too high for a Moroccan tourist, who will prefer to go it alone and rent private accommodation wherever he decides to stay.

However, the challenge of national tourism faces a much greater difficulty to be overcome: the coastal resorts, from Dakhla to Nador, will always find visitors from among their compatriots, whereas the interior of the country, that is to say the rural areas of Morocco in all their diversity, remains a terra incognita for the vast majority of Moroccans, and is likely to remain so for a long time – unless an individual and collective awareness changes for the better.

Rural Morocco should be the highlight of a vigorous national tourism

Morocco’s interior, rural Morocco, is however the heart of Morocco’s identity because the country, through its geographical location, has been blessed with a nature still preserved in its breath-taking and spectacular authenticity. With its high mountains, its rocky plateaus, its verdant plains, its oases, and of course the vast desert, Morocco offers an enormous palette to choose from for all those who look to encounter a vibrant Nature in all its diversity.

And while numerous foreigners have made and will make the thousands of kilometres from their home countries in order to walk the rock slopes of Siroua or Mgoun, or yet seek out the Saharan sands, how many young Moroccans or Moroccan families have ever crossed a single one of the oases within their country? How many have ever spent a night under the stars brightening the Moroccan desert? How many have hiked the pathways along the rivers?

But more than this, rural Morocco is also the recollection of a Morocco rooted within its territories, and also within the communities of men and women, who, since time immemorial, have written the history of their country; and, in addition, have composed the timeless body of its heritage, stone by stone, gesture for gesture, word for word.

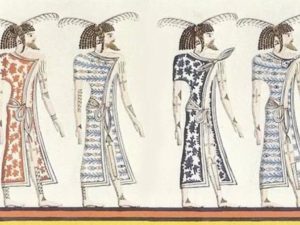

From the prehistoric etchings in the rocks to the skeletons of dinosaurs to the ancestral ways of life of the Amazigh tribes and of the Jewish and sub-Saharan communities, from the ruins of former flourishing cities, the kasbahs of former lords, from the art of music and song, from the crafts that stretch back to far distant times to the customs exchanged across the continent via the great camel caravans, from the memories of great battles and their heroes, as both conquerors and rebels …… all these facets constitute the pantheon of a teeming history of Morocco which truly finally deserves to take its rightful place in becoming the Moroccan darling of a vigorous national tourism.

However, the reality is sadly different. A Moroccan who wishes to set out to unlock the secrets of his own history in all its diverseness would find it very hard to find an organized tourist offer providing him with a trip suitable to enhancing the general knowledge of his own culture, or, in particular, to restoring his pride in being Moroccan, dazzled as he would be by the dimensions of such a flamboyant history.

South East Morocco has a golden touch

South East Morocco acts as a cruel illustration of this because, although providence has made this region the natural and historical treasure of Morocco, nothing has been done to offer the tourist any of the means required for embarking on a wonderful and unforgettable encounter with what constitutes one of the centrepieces of Moroccan heritage – perhaps even the most central one.

Who knows that the South East gave birth to an expanding medieval city, Sijlmassa, whose civilisation once shone across the entire African continent? How is it possible to venture in the footsteps of the first people to have trodden the land between Tamgroute, Ouarzazate and Errachidia? What was life in the large oases of the Dra’a valley like? How can you project yourself into the thrill of the great battles round the Tinghir mountains, such as the one at Bougafer which will have seen the anarchic resistance of the Ait Atta tribes under their chief, l’Amghar Assou or Baslam? How to rediscover the echos of the valiant warriors of the Saharan tribes of Ait Khbach or R’guibat? How to walk in the Ouarzazate of the time under the French Protectorate, a period that was just as wealthy. How to dive into the culture of the Jewish communities which made up a large proportion of South East Morocco with their very heart, soul and mind? Who still knows that the Alaouite Royal Dynasty of Mohammed VI has its roots in Tafilalet, and how to admire its expansion as far as Rabat? Who has already sensed the freshness of the Valley of Roses in Dades or in the palm groves of the Dra’a? Who can admire the skeletons of the oldest dinosaur ever discovered in Morocco, within just a few kilometres from Ouarzazate?

The South East of Morocco is golden; a delicious honey that can attract innumerable Moroccans to its territories – whole families, children, young people, anyone eager to learn about their own history and therefore delight in being the participants such a universal patrimony.

Towards a new model for territorial development

So, what needs to be done to prevent this honey from disappearing into the sands?

The key to success lies within a collective mobilisation, one that can combat this crisis and its challenges. And this means nothing less than introducing a new model for territorial development, allowing the region of Dra’a Tafilalet to become its yardstick, not simply as a new region but as a significant contributor to Morocco’s history. This model must enjoy protection and allow for an appreciation of its natural, cultural and historical heritage creating the dynamic groundwork for any future policy.

Of course, all this requires tourism professionals increasingly to orient their business plans towards discovering the pedestals of regional identity; both its Nature and its history. It also requires the local authorities to invest in the necessary infrastructures finally to create museums and eco-museums designed to allow Moroccans encounter all the region’s treasures: here dinosaurs or minerals, there for the benefit of oases or Berber crafts, elsewhere about the story of the French presence or that of the great local heroes, and even further afield to learn about the contributions made by the Jewish communities and the peoples who have come up from the South, and not to forget the history of the ksour and kasbahs.

Tourism managers will have to go beyond their logistics offering pretty photos and beautiful landscapes, and understand the virtues of territorial marketing as a cultural agenda.

And, of course, it is equally important that Moroccans themselves rediscover a thirst for their own culture, a wish to resurrect memories, a desire for historical knowledge. The Moroccan media,as well as schools, could certainly profitably play a role in this reorientation and enhancement of Morocco concentrating on its own territory, relying on all this precious and boundless natural and cultural affluence in which Morocco abounds. And this will, in fact, be the least difficult to ensure, because as with any human being, the Moroccan instinctively knows that his inner balance and the strength of his identity rest on a continuity of consciousness between his origins and his prospects.

Moroccans only need to be presented with all the elements of their glorious past, in its plurality, its truths, in its role as part of our humanity. Here in the South East of Morocco just as in every other rural area in the country.

The challenge is to awaken memories in and of Morocco

Finally, this rural Morocco, this magnificent jewel-box of Nature and memories, nowadays see itself as a bearer of an essential part of the country’s modernity since the desire for a greater ecology is now on the increase everywhere.

The slogan of the Moroccan National Tourist Office, however, is naïve since it is not only a question of organising the reconnection between Moroccans and their own country but also of reacting to a generalised lack of consciousness of Morocco’s history.

The challenge is nothing less than to open peoples’ eyes, to force them to turn away from all the superfluities of modern life in order to find the way back to the self, as a collective as well as an individual, to go and meet one’s own image, the true face of Morocco – ancestral, natural, a treasure trove.

And this … is to behold the beautiful.

Translated by : Felicity Greenlaw / Desert Majesty

2 comments

Fabulous article, extremely well written, as if this region were not already appealing enough, you have captured so much of its rich essence. I have been bringing groups to the southeast along this route since 2017. The aroma when the Valley of Roses in Boulmalne Dades is in full bloom is intoxicating. I cannot wait to resume my DiscoverYour InnerNomad tours and introduce many more people to this exceptional, but undervalued region of Morocco.

very beautiful article! Thank you for sharing with us!