And if along with them, young Algerians and young Tunisians, as well as young people from Libya and so many others scattered across the north of the African continent, had also adopted this same notion – our ancestors, the Berber …, it is highly likely that the face of the world would have been very different.

Let’s imagine that this brief refrain had entered these children’s thoughts, passed on from one generation to the next. It might mean that today the peoples of the Maghreb were naturally and historically understood as laying claim to a single and common national identity. Better still, the North African origin of anyone living or travelling in Europe would immediately be understood as synonymous with Berber identity and would become, better than a simple visa allows, a real passport to travel freely anywhere in the world.

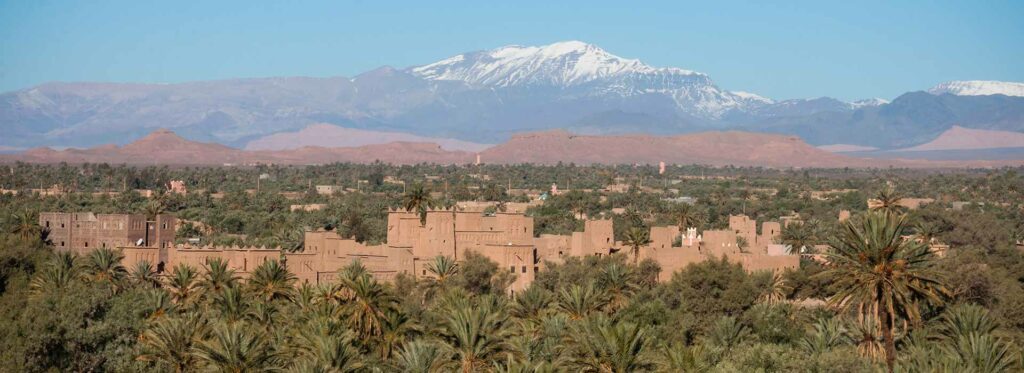

Of course, this picture is purely fictional, and nowadays exists only as an image taken from an impossible Utopia. Very early on in their existence, the populations from south of the Mediterranean have unavoidably faced an intermingling with other populations other populations from all four corners of the Earth. And owing to their geographical location, some territories such as Morocco at the junction of two continents have even served as a true crossroads. Here the cultural traces of all these successive convergences of people are more deeply embedded than elsewhere.

Peoples identity, between alchemy and story-telling

In reality, the process of elaborating on the identity of individual countries has little to do with the genealogy of their peoples, and the activities involved in this process are more often a matter of dialectics than of history. The intention is first and foremost to construct the story of a people rather than to narrate their history. The historicity of these identity narratives is clearly secondary. In the end, it is almost always a matter of an alchemy melting down human diversities, where peoples are merged together, reassembled, finally to emerge as a third, synthetic unity which permits a nation, at any given moment in its history, to become a whole and to exist.

Through a process such as this, in the 2011 preamble to its Constitution, Morocco stated that “its unity, forged by the convergence of its Arab-Islamic, Amazigh and Saharan-Hassan components has been nourished and enriched by its African, Andalusian, Hebraic and Mediterranean tributaries“.

Everywhere, in a previously communal world, was the Berber

But whatever the aim of the narrative, however human diversities have been welded together, all these forgers of a nation’s identity employ elementary materials and primitive components. Besides, everywhere in the north of the African continent, there is always the Berber. Wherever you might look across Africa from east to west, there has always been the same human substratum originating from a great common past.

This is a factual reality, an indelible one, in spite of the many attempts that have been made over the centuries to negate it, and it is unmistakable in spite of the vagueness of this enigmatic name: Berber / Amazigh.

Berber as an existing being is now indisputably considered as the oldest common denominator among a multitude of peoples and nations. Nevertheless, one undeniable observation can be made: it has been impossible for all of these peoples or nations to ascribe to this common ancestor, and therefore to share it.

The Berber paradox throughout the ages

The mystery associated with the term Berber partly explains the centuries old difficulty in creating a Berber identity acceptable to all.

Gabriel Camps, one of the most enthusiastic specialists on the subject, explains what can be called the Berber paradox in the following manner:

« In fact, nowadays there is neither a Berber language – in the sense of being a reflection of a consciously unified community, nor a Berber people and much less a Berber race. All scientists agree on this unfortunate state of affairs … nevertheless Berbers exist. »

Les berbères, mémoires et identité – Edition Errance – 1980

The historian does not explain this paradox. Faithful to his scientific discipline, he notes that the earliest Berbers certainly did not have the use of a truly common language, but that they did, at least, have at their disposal …

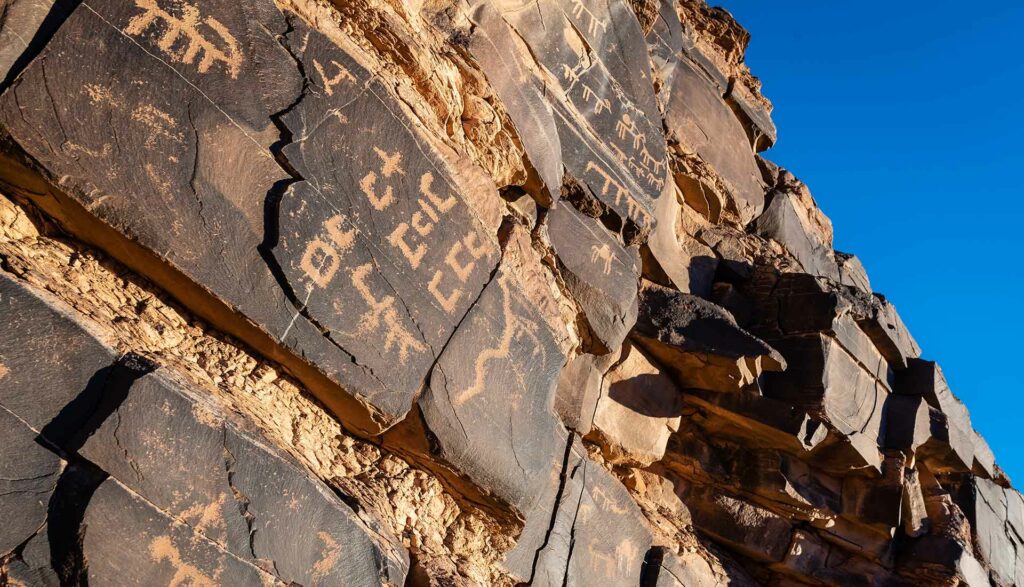

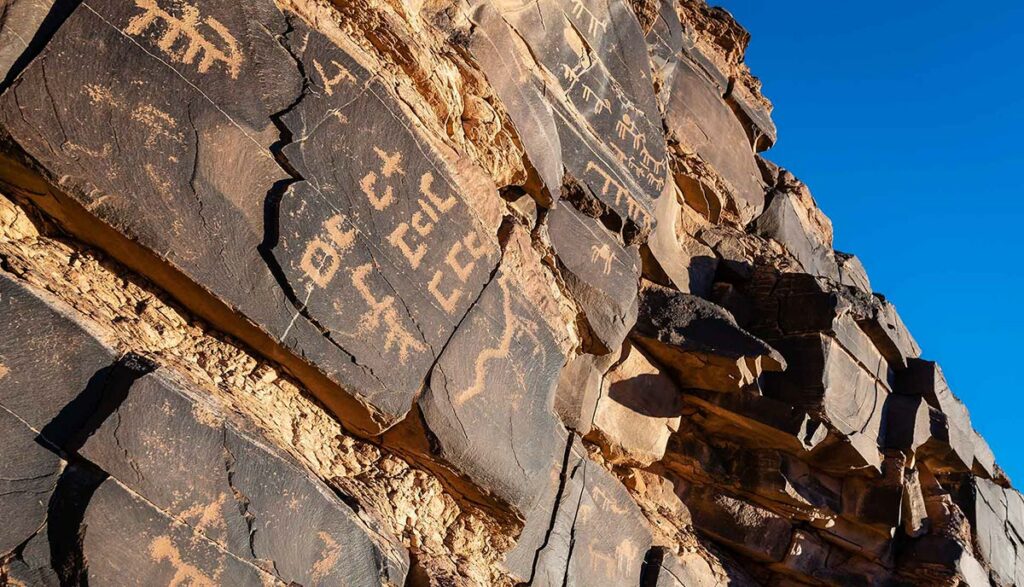

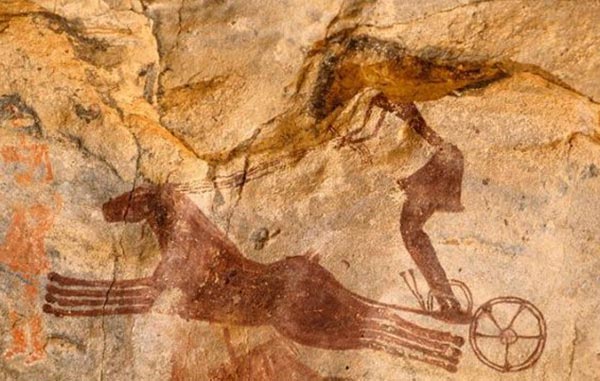

« … an original system of writing which was one widespread among them from the Mediterranean to Niger. »

Les berbères, mémoires et identité – Edition Errance – 1980

This form of writing, the Libyan, is to be found in the Tifinagh alphabet of the Touareg, the Amazigh community which has preserved the cornerstones of their Berber origins better than anyone. But the Punic alphabet, and then the Latin, and then the Arab quickly took over. This linguistic Arabisation finally brought about a transformation to a socio-cultural Arabisation at such an extent that …

« … almost all the people say they are, believe they are and as a result are Arab. But it is very rare for any of them to have even a few drops of Arab blood coursing through their veins; this new blood brought by the conquerors of the 7th century or by the Bedouin invaders of the 11th century: Beni Hilal, Beni Solaïm, and Mâquil, whose numbers, according to the most optimistic estimates, did not even reach 200,000. »

Les berbères, mémoires et identité – Edition Errance – 1980

The paradox is palpable. In all these North African countries, Punic, Jewish, Roman, Vandal, Byzantine, Arab, Turkish and finally European impulses brought about a successive and vigorous cultural mix. Yet a local identity remained alive everywhere; valid in spite of this accumulation of external contributions, and to the extent that even very early on the question was raised about what this Berber spirit was that simultaneously assimilated the foreign newcomers and yet still retained its perpetuity.

This mystery exacerbated itself in the minds of the new arrivals, constantly leading them to believe the Berber foreign to the lands they had just discovered, and to imagine him, like themselves, as having come from elsewhere, from a distant place, and simply wanting him to be something other than indigenous.

The Berber paradox throughout the ages

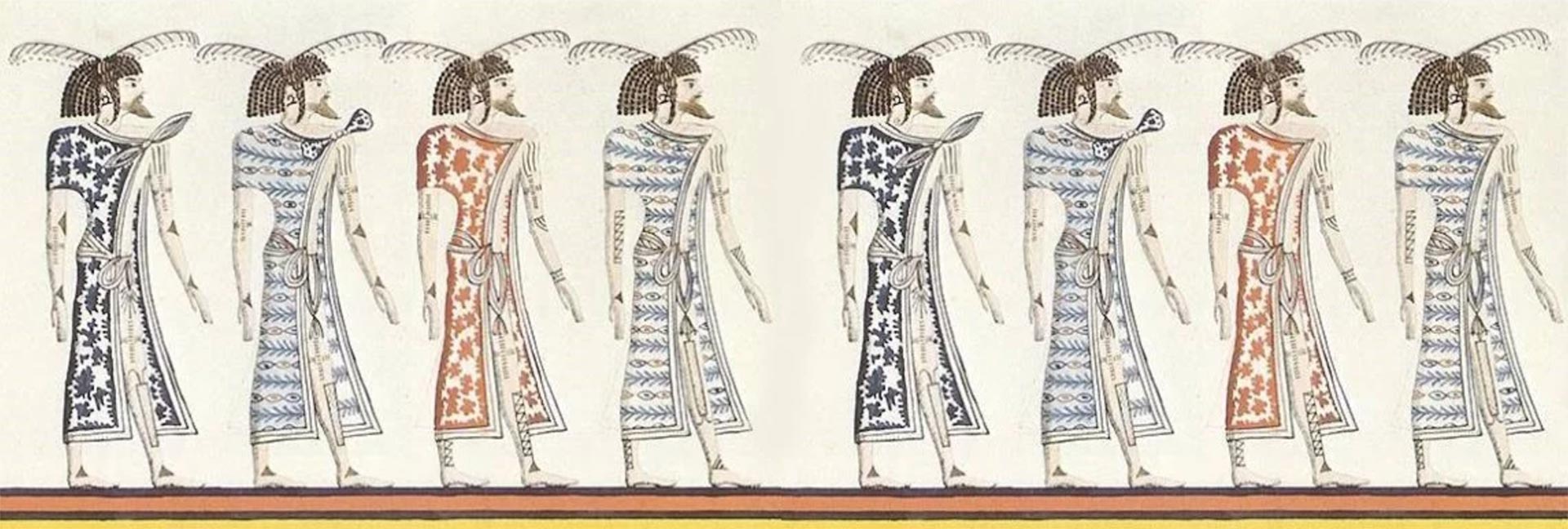

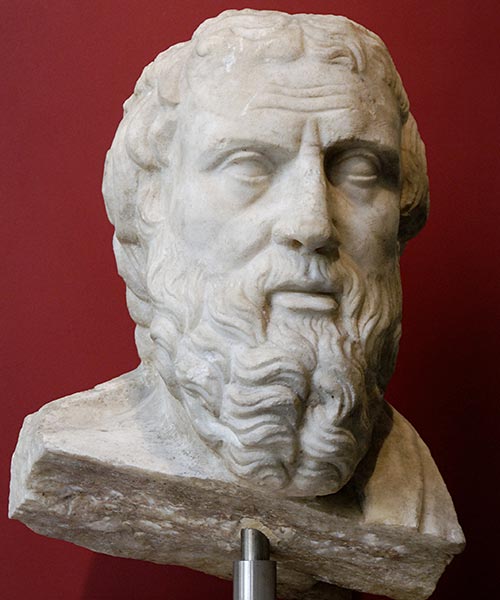

In the 5th century BC, the Greek historian and geographer, Herodotus, was the first to describe the peoples living in all the countries along the coast west of Egypt. He called them Lybians and distinguished between those who lived by the sea as nomads and those who were farmers, living in houses in the middle of mountainous and wooded landscapes, (clearly the Atlas regions), and whom he referred to as Maxyes.

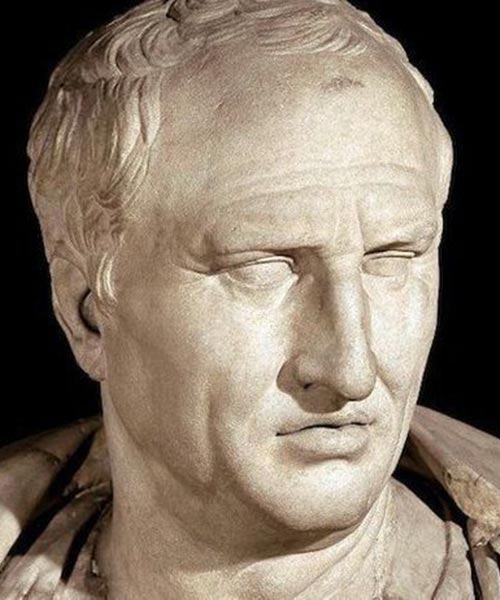

Several centuries later, his Roman counterpart, Sallust, would further define these indigenous people: the nomadic group was ultimately referred to as Gétules, while the sedentary group kept the name Lybian. According to Sallust, they had both been the inhabitants of these territories in prehistoric times; primitive hunter-gatherers perceived as …

« … coarse and barbaric who fed on the flesh of wild animals or the grass of the meadows. »

Sallust

Predictably, the Roman historian was imagining them as having been civilised by populations from the East, more precisely by the Medes and Persians, who were later to settle there.

The Medes were an ancient Iranian people who lived in a region of North-West Iran.

Gabriel Camps explains that the term Maxyes is the Greek translation of the term Imazighen (plural of Amazigh) used by the indigenous groups to identify themselves as a community. And all the foreigners coming to the territories between Egypt and the Atlantic Ocean named the inhabitants according to their own grasp of the phonetics of this primitive nomenclature: Meshwesh by the Egyptians, Mazices or Madices by the Romans and Mazigh by the Arabs.

The French historian developed a theory suggesting that the ancient accounts of the Medes tribes from the East was in fact simply the result of a deformation of the Roman name Madices, the local Imazighen; this linguistic deformation being motivated by a difficulty in conceiving that non-Romanised indigenous populations could possibly have any cultural and civilisational quality of their own.

In search of a non-viable origin

Imazighen, Maxyes, Madices, Medes… this litany of terms designating the Berber was later to be synthesized under the generic name of Moors used to designate all non-Latinised North Africans. However, observers consistently attempted to give this Berber an ascendancy external to the places he actually inhabited. And they never gave up this propensity to wish to connect this mysterious Berber to distant roots, in spite of the evidence in front of them.

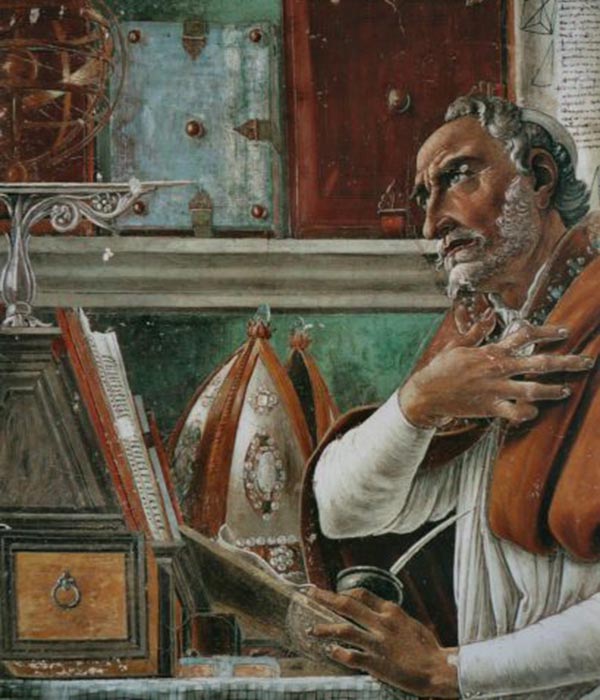

The Byzantine historian Procopius of Caesarea argues for a Phoenician origin. Saint Augustine, from his city of Hippo near Carthage, believed in the Canaanite roots in his compatriots. Another Greek historian, Strabo, saw the Moors as definitely being Indian. Herodotus states that the Imazighen are descended from the Trojans whilst Plutarch describes the great Greek hero, Heracles, as having led Mycenaean communities to Mauritania “Tingitana” (northern Morocco) in around 1500 BC.

Canaan is the name of a vast, prosperous ancient country located in the Levant region, now Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Israel.

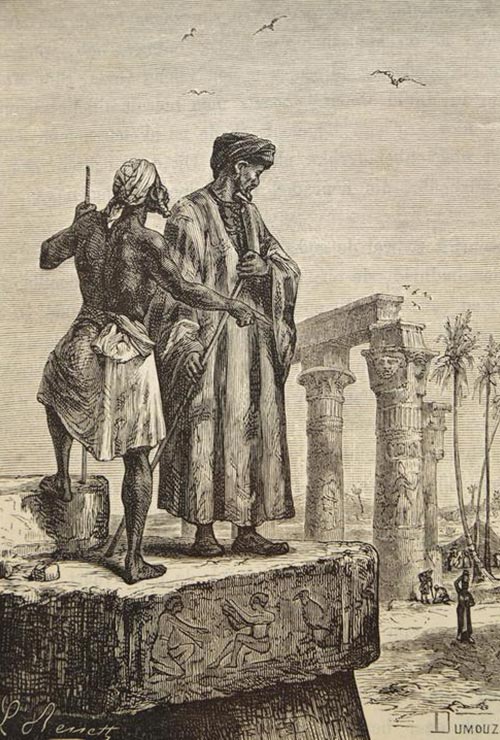

In the 14th century, the famous geographer Ibn Khaldoun was more categorical:

« The Berbers are the children of Canaan, son of Ham, son of Noah. Their ancestors were called Mazîgh. The Philistines were their parents … »

Ibn Khaldoun

The Canaanare a people of the ancient Near East settled in the southwest of the Levant along the Mediterranean coast at the end of the second millennium BC and during the first half of the first millennium BC.

European historians of the 19th century continued this frenetic search for the origins of the Berbers by occasionally giving credit to the oriental or Indian theories, even claiming that the dolmens and other megalithic monuments discovered in Algeria as being of Celtic, Gallic, and thus French, or more generally Nordic origins.

This “stranger” – indigenous for the past 9000 years

Anthropological research paints a very different picture and one that is detached from ideological ulterior motives. Of course, a human presence in North Africa, and the Maghreb in particular, dates back to very ancient times. And it has now been proven that the different representatives of Homo Sapiens that have been identified in the Maghreb – from the Neanderthal Man (from Jebel Irhoud – Morocco) through to the Aterian Man of Dar es-Soltane (Algeria) and to the Cro-Magnon type, the Man of Mechta El- Arbi of Afalou bou Rhummel (Algeria) have all three evolved locally and in their own time without any involvement from outside, and synchronically with other human evolutions elsewhere on the planet.

We will have to wait years – until 9000 B.C – until a new type of human-being from the Near East comes to settle by the ocean in large numbers. He will be called the Proto-Mediterranean and become known through the rise of a culture called “Capsian”. This newcomer will develop various off-shoots separately displaying specific morphological characteristics, with, however, two major differentiations; on the one hand, those of a robust disposition and on the other those possessing a certain dignity, which would become the standard and all of which, as to be expected, would be expressed through infinite nuances. Over the millennia this Proto-Mediterraneans spread across a large portion of the Mediterranean, from Libya to Italy.

And so Gabriel Camps was able to confirm:

« We endorse the tenet of the Capsian Proto-Mediterraneans being the first Maghrebians, meaning that we can judiciously place them at the head of the Berber lineage from some 9000 years ago! (…) These Capsians have an Eastern origin. But their arrival was so long ago that it is unreasonable to designate their descendants as truly indigenous. »

Les berbères, mémoires et identité – Edition Errance – 1980

Deploying a Berber arborescence

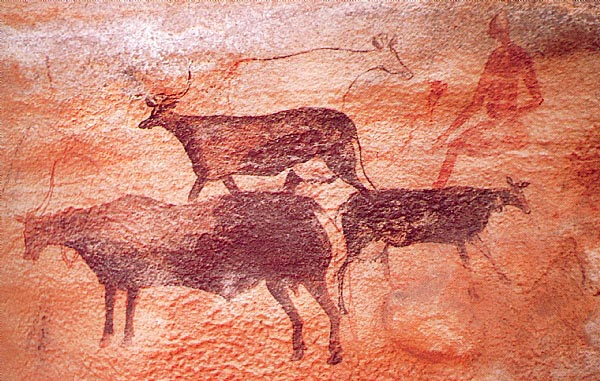

The Berbers’ genealogical roots are thus firmly anchored in the very lands where he has evolved, in the Maghreb. And like other groups of human beings inhabiting our planet, he will radically transform the Neolithic period by becoming sedentary adopting agriculture and the breeding of live-stock.

He will unremittingly welcome and assimilate the continuous human and cultural contributions from the East, from the Sahara and from the European continent via Spain. Some of these contributions will certainly prove to be more influential than others, notably the Bedouin migrations of the 11th century which seal the Arabisation of these populations. But in each era, these Maghreb territories and their human communities function as excellent crucibles of civilisation from which peoples, cultures, kingdoms and, much later, whole nations have emerged.

Throughout the millennia, this original Berber will thus be an influencer of the generalized human evolution. He will be the chariot driver who travelled, armed with his javelin, across the vast expanses of the Sahara. As a horseman, he will be the Gétule observed by the Roman conquerors, and then the nomad Garamante, true ancestor of the Touaregs, proud warrior with his long sword. Before that, he will be the Lybian described by Herodotus, or the Maxyes. He will become the Numidian of the great kingdoms of Masaesyle and Massyle with king Massinissa. The Berber will finally traverse the centuries under the name of Moors, from the most western lands of the continent to Andalusia.

Under the gaze of Ibn Khaldoum, the Berber will be seen, not as nations, but as tribes. He will be the Sanhadja, the son of Znag, the nomadic camel driver, or the Zenet, the first to become deeply Arabised. Both of them will found important dynasties such as the Almoravids, from which a vast empire would emerge, or the Merinids. He will be the Berber of the Masmoudas tribe from which will blossom the great dynasty of the Almohads whose power will reunite all the territories of origin of its Proto-Mediterranean ancestor.

The mosaic of a borderless narrative

The Berber, the Amazigh of ancient times, will not only spread out in tribes, peoples, cities or kingdoms, but it will be the source of many personalities, strong and radiant, which will engrave their name on the pages of a novel beyond any borders, truly common to all North Africans.

He will be Sheshonq I, Pharaoh of Egypt in 950 BC and founder of the 22nd dynasty, the famous king Massinissa who contributed to the victory of Rome over Carthage in 202 BC, Jugurtha, king of Numidia, Juba II, Ptolemy of Mauretania and Masuna, king of the kingdom of the Moors and Romans at the beginning of the 6th century.

Over the centuries, it will be the lot of the Berber to follow countless destinies; that of Dihya, Berber Zenet queen, or Tin Hinan, native of Tafilalet and Queen of the Tuareg of Hoggar. That of Saint Augustin, Bishop of Hippo, of Arius, a priest in Alexandria, or of Donatus Magnus, bishop of Africa, of Tertullien, a Father in the Church of Rome, of Macrin, Diadumenian, Caracalla or Aemilian, all Roman Emperors.

He becomes Tariq ibn Ziyad, an Umayyad General who set out to conquer the Iberian Peninsula in 711 and travels to unknown lands under the name of Ibn Battuta, one of the most important explorers of the Middle Ages.

He expresses his thirst for freedom under the names of Lalla Fadhma N’Soumer, Abdelkrim el-Khattabi or Assou Oubasslam, military leader of the Moroccan resistance to French colonialism.

He develops all his numerous talents as Mohand Ou Lhocine, poet and Kabyle mystic, Si Mohand Ou Mhand, Muhammad Awzalou, the Alegerian author Kateb Yacine, Mohamed Choukri, Mouloud Mammeri or Jean Amrouche, the singer Idir … and so many others, men and women of all times, all territories, all territories, crisscrossed and united through this unfathomable, unalterable thread of Amazigh origin..

The following is an unequivocal observation: In these lands of North Africa, from Egypt to the Atlantic Ocean, the Berber is at the heart of the story that is still unfolding. He is both the paper and ink of a story with neither author nor title. And yet, his spirit remains present and alive, proud and free, wherever he sets down his roots, and along with them, the tree and branches of his existences from 9 000 years ago.